Looking back, I think my first encounter with the photos of Diane Arbus must have been in one of the glossy Sunday supplements – the sort with shiny paper that makes everything ravishing, even grief and poverty.

I don't know if the glossiness conditioned my response to Arbus, whether I was influenced by the accompanying text or whether it was the work itself that upset me. Her stark, black and white photos of poor people and people with disabilities – people who would never buy a glossy Sunday supplement – seemed to have the glamour and allure of a freak-show. I shuddered and looked away.

News of a forthcoming Diane Arbus exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary disappointed me. It seemed less interesting than the accompanying, more recent work by the Tobias twins. The brochure, with colour pictures of Tobias paintings, also suggested they might have more to offer although the one Arbus reproduction, of twin girls, haunted my imagination.

Accompanied by a friend, I looked at the Tobias works with curiosity and baffled amusement, which may be the response the brothers hoped to evoke. Many seem like a cross between a kitsch version of folk art and a Gothic, Transylvanian Disney. My strongest emotion in their presence was an amused affection. I drifted on to the Arbus rooms and was transfixed by something I hadn't noticed in that early encounter with her work: tenderness.

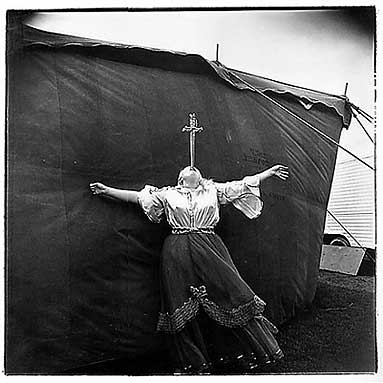

It wasn't in all the photos. Some, especially those of over-dressed rich women, seemed to expose their subjects to ridicule. I thought I glimpsed cruelty in the curve of the lips of a masked man. But in other pictures there seemed more gentleness and respect than I expected. I noticed how one of two drag queens, dressing or undressing for their act, seemed to reassure the other with a touch. I saw the dignified melancholy of a tattooed man, gazing into the distance beyond the camera. The albino girl, arms outstretched and head back as she swallowed a sword, seemed in control of her pose as she mirrored a crucifixion. So many of the subjects, often strange to the viewer or on the fringes of society, seemed to convey an inexplicable depth. Even the photographs of nudists seemed about much more than the nakedness of the subjects.

Some photographs still disturbed. I worried that the children might have disliked their portrayal – who would want to be shown in a gallery as “fat girl laughing” or to be famous as a skinny, laughing boy clutching a toy hand grenade? The extreme close-ups of babies' faces turned them into dolls or death masks. But when I came to the photos of people with disabilities which had so disturbed my teenage self, I began to ask other questions.

The subjects I'd characterised as a “freak show” looked out at me with self-confidence. They seemed as happy as any of the sitters to be recorded. So what exactly had disturbed me? Did I really think that photography was only for the beautiful, the confident or the normal (whatever that was) unless it had a proclaimed manifesto to change the world? These people just were – and were recorded.

This took me back to the photographs of August Sander and the records he made of Germany in the 1920s and 30s. Before Arbus, he had photographed people in fairgrounds and institutions, apparently letting them arrange their own poses before the camera. It was impossible to look at his photographs without the knowledge Sander lacked. I wondered how many of the people he recorded had been imprisoned, abused and killed in the Nazi regime's euthanasia programme, in concentration camps and in the bureaucratically-ordered extermination of those in the “wrong” racial groups.

My sense of recording and the influence of Sander became even stronger when I returned to the gallery for a guided tour by Alexander Nemerov, Arbus's nephew. He talked about her focus on the subjects of her portraits and the way she documented them as though in the face of impending catastrophe. I reflected later that Arbus looked more for a variety of individuals in every setting while Sander, though recording individuals, saw them more as representatives of types.

There are still problems with photography and the act of recording. For many people, the fact of being recorded and visible places them at risk. I can't help wondering whether any harm came to the subjects of Arbus's photos. It wasn't easy, in the 1960s, to be a mixed race couple, even in New York – and Arbus's caption makes it clear that the couple are married and the wife is pregnant. I wondered if the transsexuals and transvestites later regretted giving so much away or whether the disabled people in the institution suffered discomfort from the response to the publication of the photos. A photographer can try to achieve neutrality and simply observe, understandingly, a range of subjects. But as soon as the photographs are on display they enter an environment that is not neutral and which is all too eager to judge and condemn the lives of others.

Too many people still face a choice between vulnerability and invisibility. On any day I can say, without hesitation, which I would choose – but my answer isn't always the same.

No comments:

Post a Comment